Feminisation of Politics

Worldwide, women are underrepresented in managerial and leadership positions, particularly political positions. In March 2021, a report by the United Nations highlighted that 25% of parliamentarians across the world were women, a figure which increased from a mere 13.8% in 2000. Compared to education, economic and employment opportunities, the gap between men and women has narrowed the least when it comes to political representation. Working towards reducing inequality in politics would have far-reaching impacts not only for women but society as a whole. Bhalotra et al. (2021) study highlights how women have been shown to favor public goods investments, such as in education and health while also being tolerant of higher taxes, metrics which all promote growth.

When looking at the Indian state of Telangana, rife with a movement for a separate statehood since the 1900s, women have often occupied center stage in enabling this change to occur. For instance, the Telangana People’s Struggle was an anti-caste and anti-feudal movement against the Nizam of Hyderabad’s feudal regime and was inherently feminist, with numerous women leaders advocating for socio-political reform not limited to changes in the caste system, but labour protection and women’s freedom.

The movement radically expanded notions of who could participate and engage in politics, and the platforms and spaces through which this could occur. While women expanded the platform of what female dissent looked like, this political representation did not translate into large numbers in the state assembly elections of 2014, with the formation of the state. Using the LokDhaba: Indian Elections Dataset for the years 2014 and 2018, this article aims to examine how women in Telangana despite having a sizeable presence in civil society, are negligible in numbers at the assembly level through the lens of political parties, the number of contesting candidates and security deposits lost.

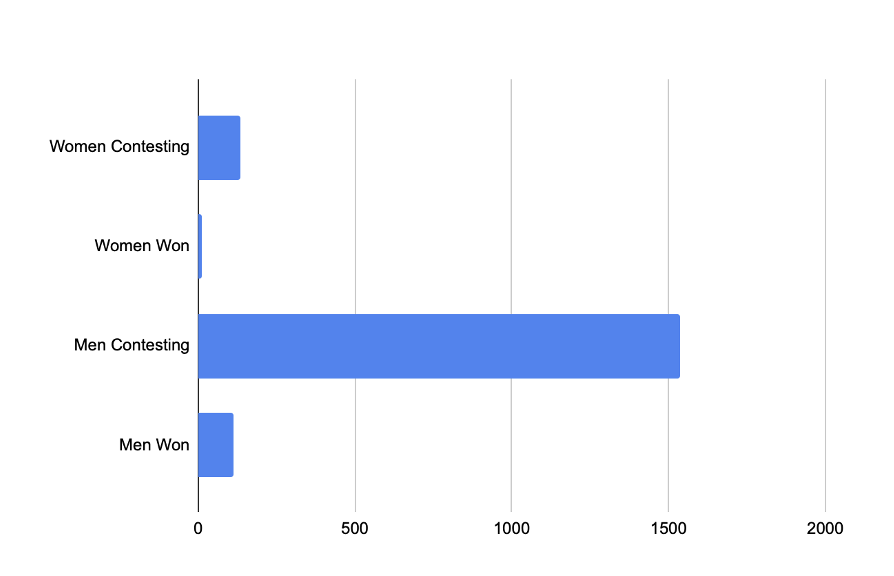

Women Candidates Contesting in State Assembly Elections in 2014 and 2018

Data from the LokDhaba Dataset revealed a total of only 134 women contested in the assembly elections of 2014, in contrast to 1537 of their male counterparts. Out of these 134 women a mere nine won, compared to 110 male winners. The same is depicted in the chart below.

Figure 1 Source: Lok Dhaba, Trivedi Centre for Political Data

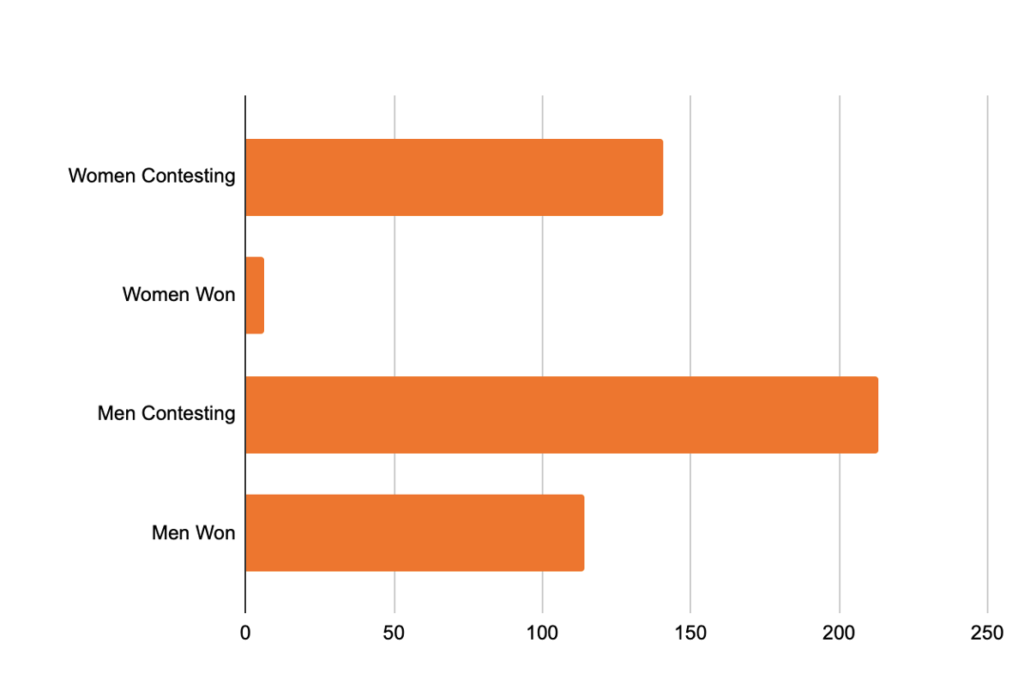

Following a similar trend as seen in the chart below, assembly elections of 2018 had the number of women contesting at a dismal 140 out of 1822 candidates, compared to 1681 men contesting. Of these 140 female candidates, a mere six won.

Figure 2 Source: Lok Dhaba, Trivedi Centre for Political Data

The low number of women parliamentarians goes beyond politics to reflect community attitudes. Patriarchal structures limit the number of women in politics. An Amnesty International report (2020) showed the scale of abuse female politicians in India face on social media platforms. Sexist remarks are often hurled at women contesting, regarding their appearance, clothing, or experiences, and is more than often one of the reasons which discourage women from participating in governance. This potential factor could explain the low number of women contesting in politics, as societal norms have too often relegated women to the domestic sphere, leaving governance and leadership positions in the hands of men.

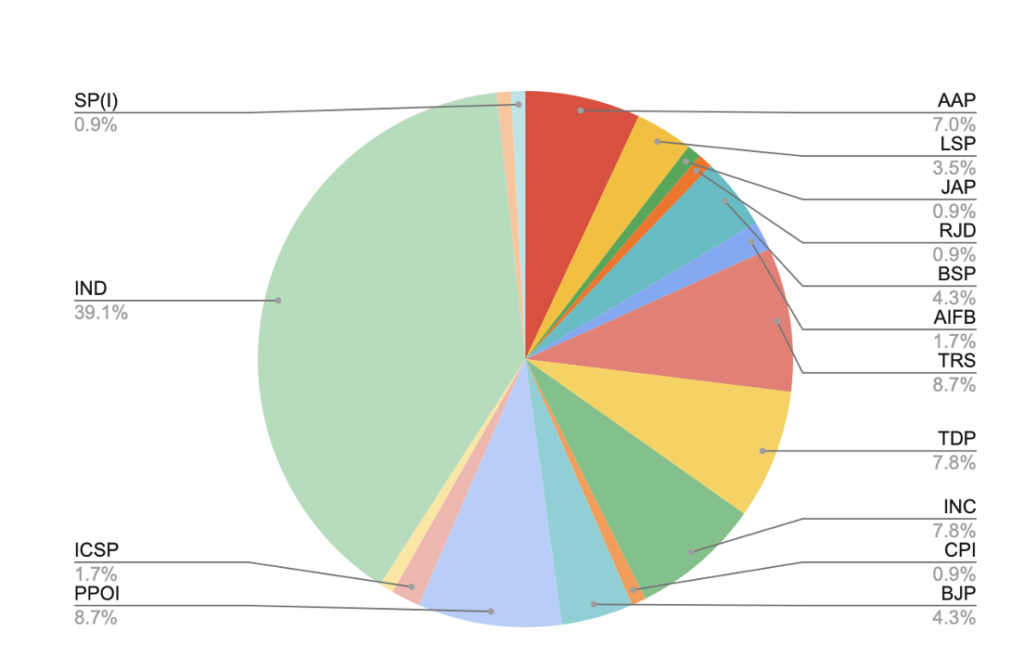

Political Parties and Women Candidates

In a democracy, political representation is an inherent aspect of political participation. In this regard, whether women are able to participate politically is dependent on political parties. While political parties in manifestoes often promise to safeguard the safety, health, and financial security of women, their commitment to reducing the gender gap ends when it comes to providing tickets to female candidates.

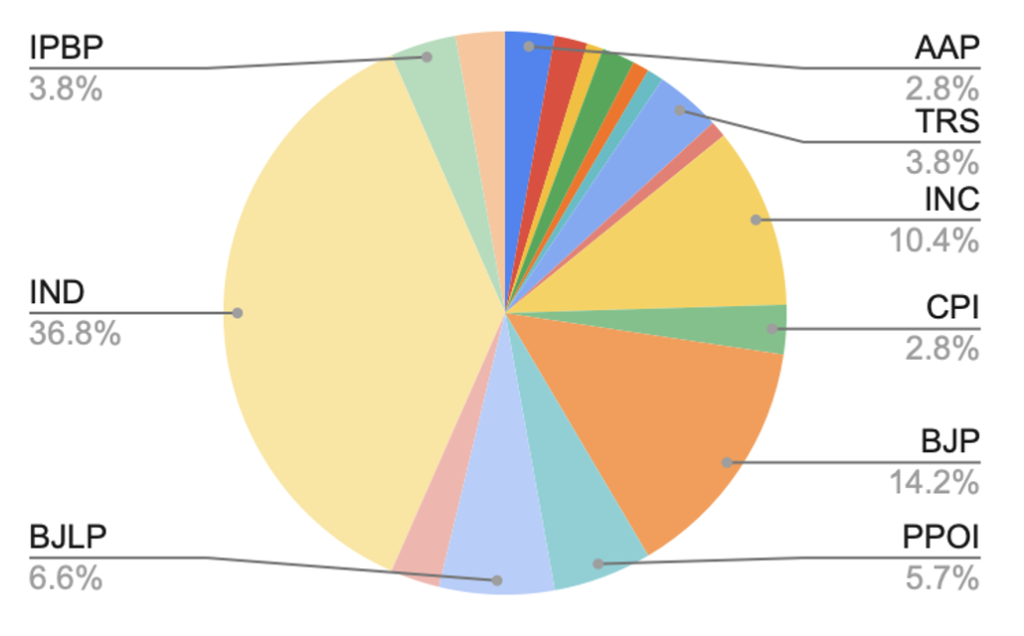

For the year 2014, the chart below depicts the tickets given by political parties to female candidates in percentage terms. The Telangana Rashtra Samithi handed out 10 tickets to women, followed by nine tickets provided by Indian National Congress. What is interesting to note is that 39.1% of women candidates chose to run as independents, due to the lack of support from political parties. Across parties, there is a meager representation of women in terms of tickets

Figure 3 Source: Lok Dhaba, Trivedi Centre for Political Data

allotted, forcing women to run as independent candidates. By running as independents, many female candidates are able to run on lists affiliated with civil society organizations and other grassroots-level movements thereby aiming to challenge status quo politics which could potentially pave the way for a better future.

Similarly in the year 2018, The incumbent Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS), headed by K Chandrasekhar Rao, provided only four tickets to women, which also reflects the state of Telangana, one in which women have been excluded from decision-making. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) performed the best as it gave tickets to 15 women, including tickets to three women each from the SC and ST communities. Indian National Congress (INC) provided only 11 tickets to women, but most of them were provided to candidates from political dynasties. The Telugu Desam Party decided to give the Kukatpally ticket to Nandamuri Suhasini, the daughter of late actor-politician Nandamuri Harikrishna and granddaughter of TDP founder NT Rama Rao. Dynastic politics is associated with a double form of exclusion; first by creating a birth-based political class, and second by increasing the representation of certain groups within this political class. Despite this, it has been used as a channel to increase the representation of women who have not found a space in politics through normal mechanisms. In such a society, not having dynastic ties could serve as a form of inequality. In order to embrace and promote genuine female empowerment and leadership, parties must redirect their efforts by encouraging higher levels of female participation in governance from marginalized communities. Only then can they achieve equitable representation of women from all sections of society.

Figure 4 Source: Lok Dhaba, Trivedi Centre for Political Data

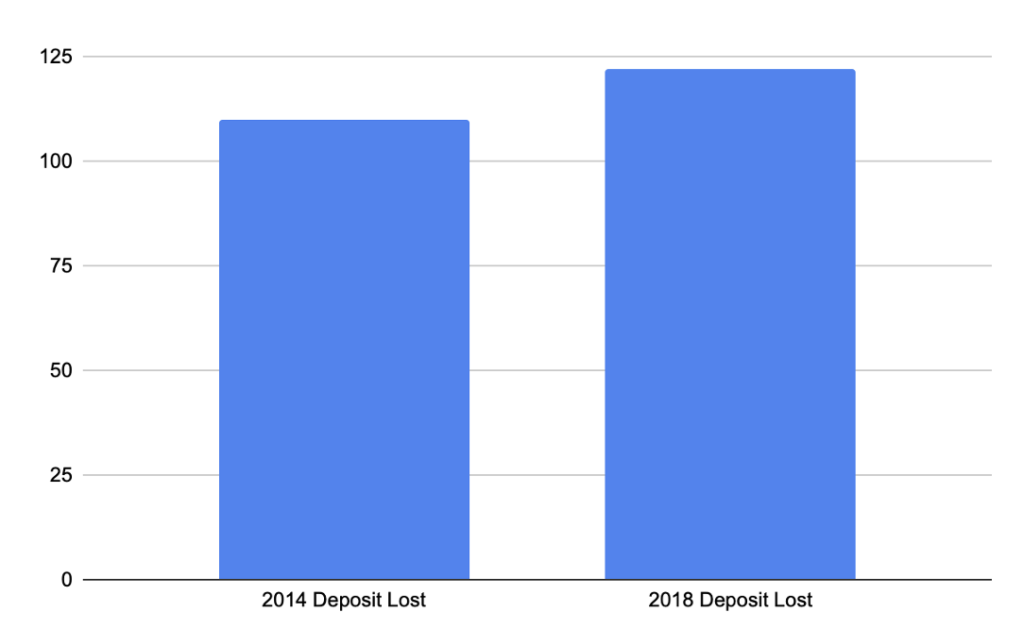

Deposits Lost by Female Candidates

Stereotypical societal and gender norms and discriminatory work attitudes have been well-known factors that restrict women from participating in politics. However, another deterrent is finances. Security deposits are required to be made by nominees when standing for elections, and are forfeited, if they fail to obtain less than one-sixth of the votes.

Figure 5 Source: Lok Dhaba, Trivedi Centre for Political Data

While this was designed to reduce the fraction of non-serious contenders participating in electoral politics, it has widened the gender gap. Out of the 134 female candidates contesting in 2014, 110 of them lost their security deposits. Similarly, for the year 2018, out of the 140 women contestants, 122 lost their deposits as they received less than one-sixth of the votes in their constituencies. Forfeiture of security deposits is often used by political parties to field fewer women candidates while safeguarding their male counterparts; altogether limiting the scope of women entering politics. Monash researcher Dr. Umair Khalil analyzed state elections in India from 1977 to 2019 and studied how deposit forfeiture inadvertently contributed to the gender imbalance in Indian politics. The findings highlighted that female candidates who forfeit their deposit were 60% less likely to recontest in the following elections, and there was no such impact on their male counterparts (Khalil, 2022). Across Indian states, systemic barriers such as forfeiture of deposits add to the hurdles that challenge women from entering the political arena.

Way Forward

While the number of women contesting, as well as being elected, has steadily risen, there is still a need for continued and dedicated action on this front. Furthermore, the gender gap between men and women has been narrowing in the fields of education, and employment; it is of utmost urgency that it reduces political representation too. Irrespective of the political regime in a country, political parties act as gatekeepers to positions of political power. As a result of this, parties must realize the critical role they play as gatekeepers in women’s political participation and in turn make changes in the organization structure to complement women’s entry into politics. This would have a significant impact on the future female leaders in the country.

About the Author

Simran Sharma is an undergraduate at Ashoka University and is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s in Economics and Political Science.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ananay Agarwal from the Trivedi Centre for Political Data for his feedback and suggestions.

References

Bhalotra, S., Bhaskaran, T., Min, B., & Uppal, Y. (2021). Women Legislators and economic performance. Warwick Economics Research Papers. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/workingpapers/2021/twerp_1354_-_bhalotra.pdf

New study shows shocking scale of abuse on Twitter against women politicians in India. Amnesty International USA. (2020). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.amnestyusa.org/press-releases/shocking-scale-of-abuse-on-twitter-against-women-politicians-in-india/

United Nations. (2021). Proportion of women parliamentarians worldwide reaches ‘all-time high’ . United Nations. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086582

Khalil, Umair. “What Stops Women Entering Politics?” Impact: Monash Business, May 3, 2022. https://impact.monash.edu/diversity/female-candidates-stymied-entering-politics/.

Disclaimer

This article belongs to the author(s) and is independent of the views of the Centre.