27 January 2022 | 2 min read

The world of cabinet reshuffles

A cabinet reshuffle occurs when government ministers are moved between posts. They can be relatively minor – for example, when a minister resigns and needs to be replaced – or they can entail significant transformations such as several cabinet ministers changing departments or leaving government, or ministerial roles and sometimes even entire departments being created or removed. Cabinet reshuffles happen for a variety of reasons such as party management (to reward loyalty and punish dissent), performance management (to manage the overall efficiency of different departments), or to signal policy shifts.

Cabinet stability is of significant interest as it reflects the effectiveness of the executive branch. Regularly changing a department’s leadership can harm policy implementation. Excessive turnover makes it difficult for individual ministers to build up expertise about their department and makes it harder for the parliament to hold ministers accountable for the outcomes of their actions.

In this piece, we explore some metrics to judge the stability of the council of ministers using TCPD’s Indian Council of Ministers (ICoM) dataset between 1990 and 2021. The analysis has been conducted on a subset of the ICoM dataset with the following exceptions:

- The 9th Lok Sabha (1989-1991) is not considered (data is incomplete)

- The 17th Lok Sabha (2019 – present) is not considered (ongoing, therefore incomplete)

- Prime Ministers are not considered (PMs are not properly accounted for in the dataset)

Interpreting the data

Tenure reflects the amount of time a minister held office. Using the appointment dates provided in the dataset, we calculate the tenure (expressed as number of years) for each appointment. Tenure alone would give us a slightly misleading picture, therefore it is important to account for the outliers in the dataset, for instance the 11th (1996-97) and 12th (1998-99) Lok Sabhas, each of which lasted less than 2 years. We have used the appointment dates to arrive at a measure of the length of each session as well. We expect shorter tenure durations to be associated with greater cabinet instability.

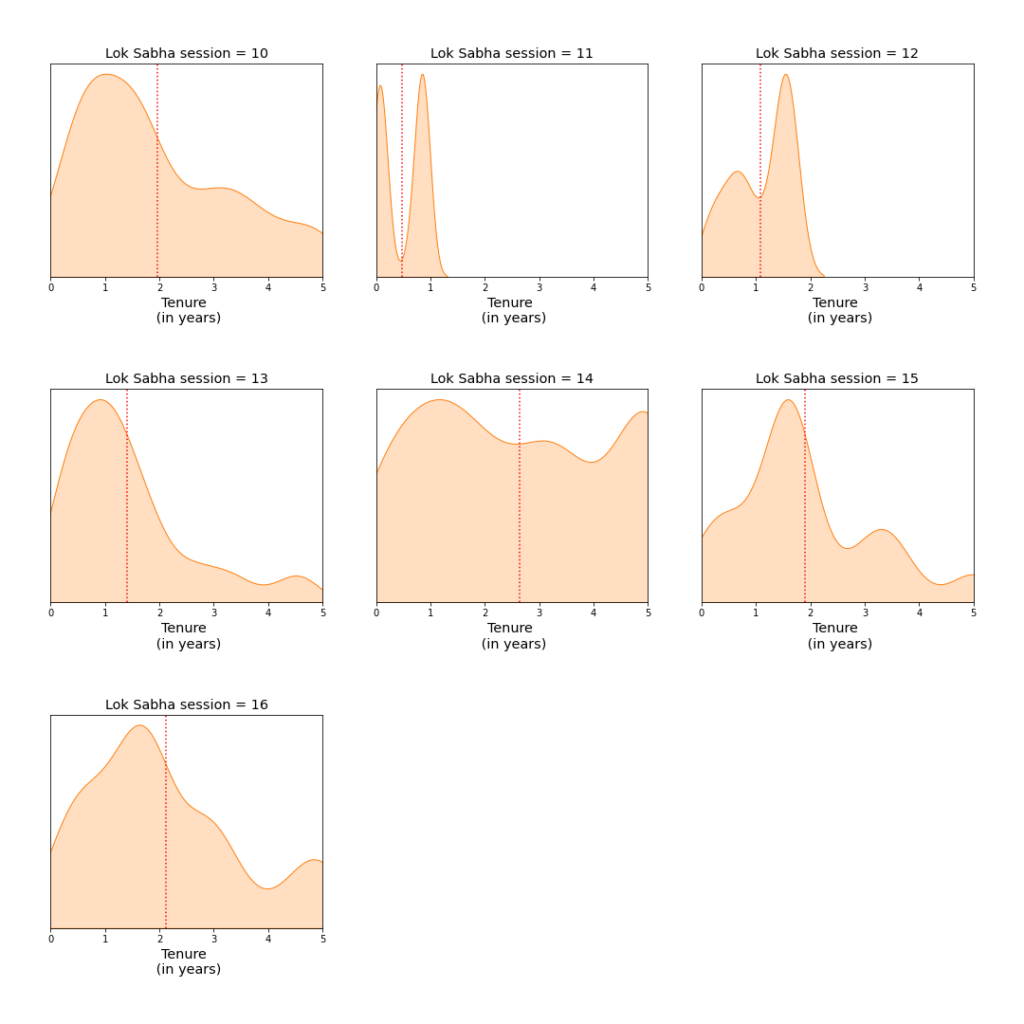

Figure 1: Distribution of tenure length across assemblies

Note: Red dotted line reflects average tenure duration for the given assembly

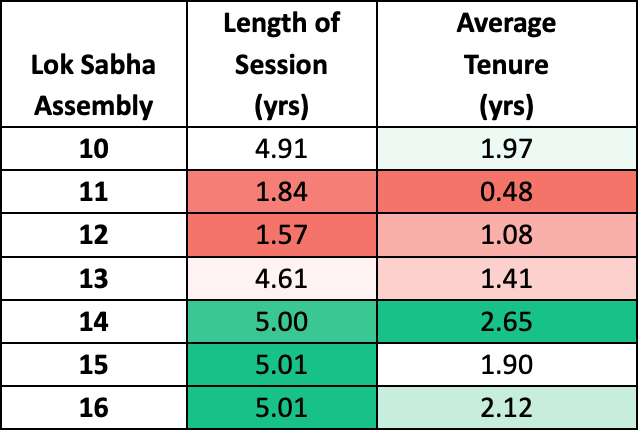

Table 1: The length of session and average tenure disaggregated by assembly

Findings

The data from Table 1 and Figure 1 reflects that the 11th Lok Sabha had the shortest average tenure, whereas the 14th (2004-09) Lok Sabha witnessed the longest average tenure per appointment. It clearly shows the instability of the late 1990s during the 11th and 12th Lok Sabha, a trend which seems to extend to even the 13th (1999-2004) Lok Sabha.

There are a couple of noteworthy aspects in this data:

- The average tenure during the relatively stable Lok Sabhas hovers around 2 years (excluding the outliers).

- The 11th Lok Sabha, despite being marginally longer, has a shorter average tenure in comparison to the 12th Lok Sabha.

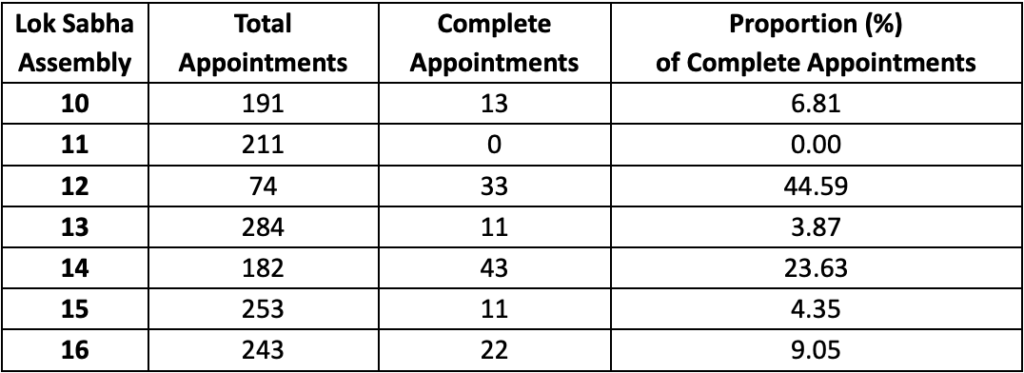

We extend this analysis by presenting a breakdown in the following table of the count of appointments for each Lok Sabha, classified according to how many appointments were ‘complete’ (i.e, lasted the span of the entire session).

Table 2: Total appointments and complete appointments disaggregated by assembly

Figure 2: Total appointments and complete appointments disaggregated by assembly

Figure 3: Complete appointments expressed as a proportion of total appointments for each Lok Sabha assembly

The noteworthy trends from the above data are as follows:

- For most sessions, Figure 3 indicates that the proportion of complete appointments is quite low – less than 10%, with most sessions clustering around 5% of complete appointments. This supports the idea that the average tenure is in the range of 2 years. A deeper look at the details of such complete appointments revealed that the majority (>90%) of these were Cabinet Ministers or Ministers of State while Ministers of State with Independent Charge and Deputy Ministers formed the remaining minority of <10% of complete appointments.

- In Figure 2 we observe the extent of instability within the 11th Lok Sabha, with 0 appointments that lasted across the span of the session. This stands in contrast to the 12th Lok Sabha. Although both of these lasted just under 2 years, the data clearly indicates the 11th Lok Sabha was uniquely unstable.

- On the other hand, the 14th Lok Sabha stands out as an outlier with nearly a quarter of total appointments lasting the span of the whole session. While excessive turnover may indicate instability in the government, a very low turnover may hint at a sense of stagnancy in the council but this hypothesis warrants more examination.

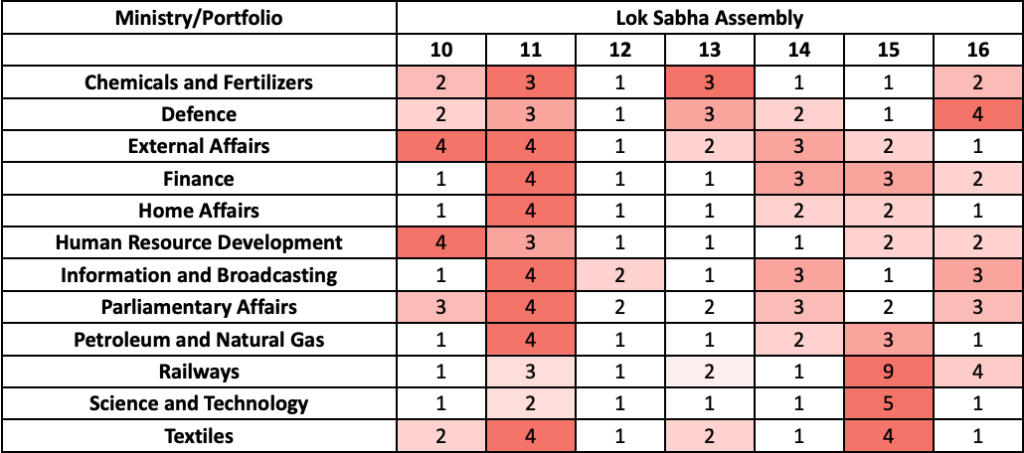

Another useful metric to gauge the stability of the cabinet is the number of Cabinet Ministers appointed for each ministry during a Lok Sabha session:

Table 3: Number of Cabinet Minister appointments for each Ministry, disaggregated by Lok Sabha Assembly

(Row-wise heat map)

This table shows the number of Cabinet Minister appointments for key ministries for which data is available. It should be noted that a cabinet reshuffle (i.e change in portfolio for a minister) counts as a new appointment. Table 3 helps us identify particularly unstable terms (such as the 11th Lok Sabha) as well as other major reshuffles that may take place in otherwise stable terms, such as the cluster of reshuffles in the 15th (2009-14) Lok Sabha. We see that the 11th Lok Sabha had, on average, close to 4 reshuffles for the rank of cabinet minister for each ministry, while the similarly-long (in duration) 12th Lok Sabha’s average is close to 1. The average for a 5-year-term is around 2 cabinet ministers per ministry.

However, the analysis of ministry appointments is not a straight-forward task for ministry names, their structure, and composition can change over the years, making it difficult to examine the trajectory and performance of the ministry over time. For instance, the Ministry of Labour was renamed after the 13th Lok Sabha session to the Ministry of Labour and Employment, which broadened its scope. While there are cases of ministries being trivially renamed, there are cases where the ministry functions have been split to form two different portfolios with separate cabinet ministers for each. For instance, the Steel and Mines portfolio was split into two––focussing separately on Steel and Mines––from the 9th Lok Sabha to the 11th Lok Sabha with both being under the same minister until the 14th Lok Sabha when they were assigned to different ministers. This particular example illustrates the hurdles in gauging the competence and performance of ministers who, due to a merger or a split in portfolios, may have to take on completely new responsibilities for which they are unsuited.

Conclusion

In this article, we have used the Indian Council of Ministers dataset to analyse the stability of the Indian cabinet between the 10th (1989-91) and 16th (2014-19) Lok Sabha. Using the metrics defined above, we were able to identify two outliers – the 11th (1996-97) Lok Sabha and the 14th (2004-09) Lok Sabha. The 11th Lok Sabha stands out as uniquely unstable, even when contrasted against the 12th (1998-99) Lok Sabha of comparable length. On the other hand, the 14th Lok Sabha’s unprecedented stability possesses a hint of stagnation within the cabinet. The goal of this article is to succinctly highlight notable trends represented in the data. The socio-political and strategic factors influencing these trends warrant separate analysis.

About

Shivam Gangwani is currently working as an intern at TCPD. He graduated from Delhi University with a B.A. (Hons) in Economics. His interests lie in applications at the intersection of social sciences and technology.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude towards Aishwarya Sunaad and Priyamvada Trivedi for their feedback and suggestions, and Neelesh Agrawal and Srishti Gupta for providing direction and insights that shaped this article.

References

Neelesh Agrawal, Saloni Bhogale, Aritro Bose, Mohit Kumar, Dipanita Malik and Omkar Mishra. 2021.

“TCPD-ICoM: Indian Council of Ministers Dataset 1.1″, Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University.

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/government-reshuffles