Shreyashree Nayak

28 August 2021 | 2 min read

Tamil Nadu’s politics has changed deeply since the demise of its former Chief Minister and ADMK party leader, J. Jayalalitha, in 2016. Her passing truly marked the end of an era in Tamil politics, shaped by the role, stature and politics of one of India’s most formidable women politicians. She ran the state government four times, between 1991 and 2016. Her style of governance – populist, personalized and welfarist – epitomized a political culture and style that have become pervasive in many other states, as well as in national politics1. Her career should not however obfuscate the fact that women have historically been strongly under-represented in Tamil Nadu politics, a domain that remains dominated by men.

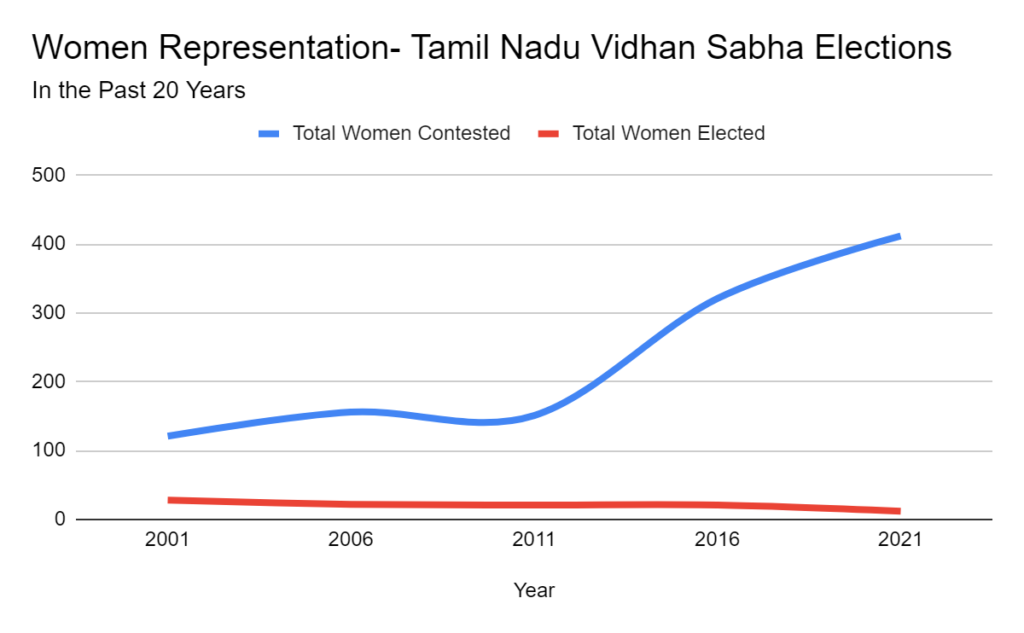

In the last 2021 elections, only 12 women were elected, in an assembly of 234 – seven from the DMK alliance and five from the AIADMK alliance. The number of women in the Tamil assembly has in fact reduced significantly, even though women outvoted men2. In the 2016 election, 22 constituencies did not have a single female candidate. Apart from the representation of women in state cabinets and during the electoral process, the same parties that expressed support to the Women Reservation Bill fielded only 8.45 per cent of women in the 2016 polls (320 women candidates out of 3,783).3

Total Women Contested vs. Elected in Tamil Nadu Vidhan Sabha Elections (2001-2021)

(Source- TCPD-Lok Dhaba- Political Career Tracker and Indian Elections Dataset- TCPD-IED)

Just like in Assam and Kerala, women in Tamil Nadu have come a long way in the socio-economic realm. The political involvement as a result has also witnessed a positive effect. The Special Summary Revision-2021 from the Election Commission shows there are 10 lakh more female (3,18,28,727) than male (3,08,38,473) voters in Tamil Nadu. If past trends continue, women may vote in greater numbers than men, indicating their vigorous political participation4. However, these favourable numbers do not translate into more women representation. Parties are scrutinized as key gatekeepers for women’s political recruitment5. These trends are concerning, especially coming from a state that was led by a woman politician for more than a decade. The state is also known for having one of India’s first documented women legislators, Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy6.

High Interest, Low Participation – When there is a will, there isn’t always a way.

50 per cent reservation for women in urban and rural local governments has helped raise female representation in local governments. Leaders have been successful in advocating women representation in local politics. Unfortunately, the political career for most women ends there. The percentage of women MLAs has stayed in the single digits for all but two assemblies since 19627. The paradox of doing well in gender indexes but having a lack of representation in politics can be understood through the resilient patriarchal structure of the state’s society, which has extended from the personal into the political.

Without at least 40% presence in the assembly, the opinions of women are often drowned out by the male majority8. The path of politics has seen various women leaders rise but rigid structures, as well as the threat of violence, has prevented women from taking the forefront in Tamil Nadu Politics. This has led to women-centric policies not being a top priority for both voters and politicians. This was represented in a survey conducted by the Association of Democratic Reforms. Empowerment of women and security was prioritized as the 11th most important issue, much behind issues like traffic congestion, pollution, among other issues9.

Tamil Nadu politics has always been male-dominated, with politicians averse to providing women leaders agency to gain individual popularity. A survey conducted by IndiaSpend in six districts of Tamil Nadu studied the political careers of women policymakers. The survey examined 32 women-led panchayats in six districts. It found that “30% women said they would like to contest the upcoming panchayat elections even when their seat was an unreserved one. Also, 15% women said they would like to enter mainstream electoral party politics if given a chance.”

Since its initial reservation of 33% for women in local governments, at least 18,244 women from the general category, 6,408 from scheduled castes and 416 from scheduled tribes have become panchayat heads in Tamil Nadu, according to data from the Tamil Nadu State Election Commission10. However, there are barely any women who have been successful in climbing the political hierarchy which is entrenched in sexism.

The survey also found that those interested in joining active politics eventually return to the domestic sphere after their panchayat terms11. This is because they are dissuaded both by the patriarchs of their family as well by the men in their families otherwise involved in politics. Men in their families view the panchayat presidency as a male domain and therefore, believe that the women must concede and vacate the seat for them12. District units of political parties can play a vital role in advancing the political career of various women panchayat members through effective recruitment. However, it becomes the biggest challenge due to the absence of women district secretaries, making the male-dominated sphere reluctant to give them a place in their party13.

Therefore, few women are successful in climbing the political ladder. Those who manage to break the shackles of domestic and professional patriarchy are expected to compromise in front of their male counterparts, rarely given any agency, or are subject to violence as seen in the brutal murder case of Menaka, who was the Dalit president of Urapakkam Panchayat, near Tambaram, a Chennai suburb14. Even J. Jayalalitha was subjected to verbal and physical abuse during her political career. The role of rigid barriers and violence against women politicians answers the paradox of high voter participation, low representation of women in Tamil Nadu’s politics. The growing political consciousness among women with the rise in women voters is not supported by the lack of women candidates fielded by major political parties. Therefore, the political arena fails to address the patriarchal barriers in electoral politics that make it difficult to stand as a candidate in the first place.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Professor Gilles Verniers for helping me draft this article and for editing the content. I also would like to thank Professor Maya Mirchandani for guidance and Ananay Agarwal for assistance and help.

References:

Ananay Agarwal, Neelesh Agrawal, Saloni Bhogale, Sudheendra Hangal, Francesca Refsum Jensenius, Mohit Kumar, Chinmay Narayan, Basim U Nissa, Priyamvada Trivedi, and Gilles Verniers. 2021.“TCPD Indian Elections Data v2.0″, Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University.

1 Varadarajan, Siddharth. “With Jayalalithaa’s Death, Politics in Tamil Nadu Is Set to Turn Fluid, Unpredictable.” The Wire, December 6, 2016.

2 Ramakrishnan, Sushmita. “Glaring Gap: Only 5 per cent of Elected Representatives Are Women in Tamil Nadu.” The New Indian Express, May 4, 2021

3 Ramesh, Mythreyee. “Number of Women Poll Contestants Shows the Massive Gender Disparity in Tamil Nadu Politics.” The News Minute, May 4, 2016.

4 Krishnaswamy, Tara. “State of Paradox: Missing Women in Tamil Nadu’s Political Landscape.” The Times of India, March 9, 2021.

5 Spary, Carole. “Women candidates, women voters, and the gender politics of India’s 2019 parliamentary election”, Contemporary South Asia 28, no.2 (2020), 223-241

6 Yadav, Karan. “Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy: The Unsung Feminist of India.” India Today, July 30, 2019.

7 Krishnaswamy, Tara. “State of Paradox: Missing Women in Tamil Nadu’s Political Landscape” The Times of India, March 9, 2021.

8 Krishnaswamy, Tara. “State of Paradox: Missing Women in Tamil Nadu’s Political Landscape” The Times of India, March 9, 2021.

9 Ramesh, Mythreyee. “Number of Women Poll Contestants Shows the Massive Gender Disparity in Tamil Nadu Politics.” The News Minute, May 4, 2016

10 Rao, Bhanupriya, IndiaSpend.“What Stops Women Leaders in Tamil Nadu from Moving up the Political Ladder.” Business-Standard, June 30, 2018

11 Rao, Bhanupriya, IndiaSpend.“What Stops Women Leaders in Tamil Nadu from Moving up the Political Ladder.” Business-Standard, June 30, 2018

12 Rao, Bhanupriya, IndiaSpend.“What Stops Women Leaders in Tamil Nadu from Moving up the Political Ladder.” Business-Standard, June 30, 2018

13 IndiaSpend. “Why 277,160 Women Leaders Remain Invisible To Tamil Nadu’s Political Parties.” BehanBox, April 3, 2021.

14 Manikandan, K. “Dalit Panchayat President Killed in Chennai Suburb.” The Hindu, June 28, 2016.